In 2017, detectives working a chilly case on the East Bay Regional Park District Police Division obtained an thought, one that may assist them lastly get a lead on the homicide of Maria Jane Weidhofer. Officers had discovered Weidhofer, useless and sexually assaulted, at Berkeley, California’s Tilden Regional Park in 1990. Almost 30 years later, the division despatched genetic info collected on the crime scene to Parabon NanoLabs—an organization that claims it may possibly flip DNA right into a face.

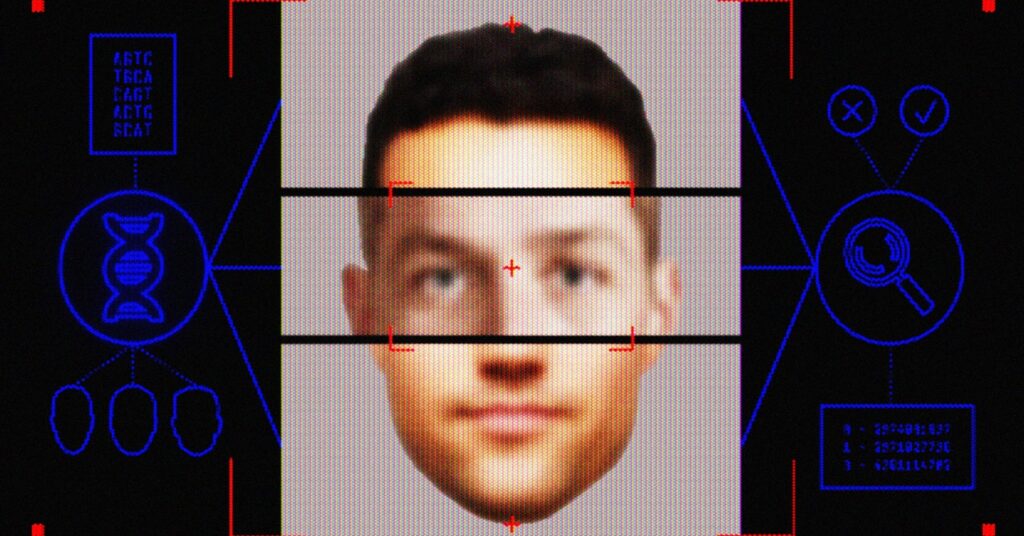

Parabon NanoLabs ran the suspect’s DNA by its proprietary machine studying mannequin. Quickly, it offered the police division with one thing the detectives had by no means seen earlier than: the face of a possible suspect, generated utilizing solely crime scene proof.

The picture Parabon NanoLabs produced, referred to as a Snapshot Phenotype Report, wasn’t {a photograph}. It was a 3D rendering that bridges the uncanny valley between actuality and science fiction; a illustration of how the corporate’s algorithm predicted an individual may look given genetic attributes discovered within the DNA pattern.

The face of the assassin, the corporate predicted, was male. He had truthful pores and skin, brown eyes and hair, no freckles, and bushy eyebrows. A forensic artist employed by the corporate photoshopped a nondescript, close-cropped haircut onto the person and gave him a mustache—an inventive addition knowledgeable by a witness description and never the DNA pattern.

In a controversial 2017 choice, the division revealed the expected face in an try to solicit ideas from the general public. Then, in 2020, one of many detectives did one thing civil liberties consultants say is much more problematic—and a violation of Parabon NanoLabs’ phrases of service: He requested to have the rendering run by facial recognition software program.

“Utilizing DNA discovered on the crime scene, Parabon Labs reconstructed a doable suspect’s facial options,” the detective defined in a request for “analytical help” despatched to the Northern California Regional Intelligence Heart, a so-called fusion middle that facilitates collaboration amongst federal, state, and native police departments. “I’ve a photograph of the doable suspect and wish to use facial recognition expertise to determine a suspect/lead.”

The detective’s request to run a DNA-generated estimation of a suspect’s face by facial recognition tech has not beforehand been reported. Present in a trove of hacked police data revealed by the transparency collective Distributed Denial of Secrets and techniques, it seems to be the primary identified occasion of a police division trying to make use of facial recognition on a face algorithmically generated from crime-scene DNA.

It probably received’t be the final.

For facial recognition consultants and privateness advocates, the East Bay detective’s request, whereas dystopian, was additionally fully predictable. It emphasizes the ways in which, with out oversight, legislation enforcement is ready to combine and match applied sciences in unintended methods, utilizing untested algorithms to single out suspects based mostly on unknowable standards.

“It’s actually simply junk science to think about one thing like this,” Jennifer Lynch, normal counsel at civil liberties nonprofit the Digital Frontier Basis, tells WIRED. Operating facial recognition with unreliable inputs, like an algorithmically generated face, is extra more likely to misidentify a suspect than present legislation enforcement with a helpful lead, she argues. “There’s no actual proof that Parabon can precisely produce a face within the first place,” Lynch says. “It’s very harmful, as a result of it places individuals liable to being a suspect for against the law they didn’t commit.”