At 10 p.m., a hospital technician pulls right into a Walmart parking zone. Her 4 children — one nonetheless nursing — are packed into the again of her Toyota. She tells them it’s an journey, however she’s terrified somebody will name the police: “Insufficient housing” is sufficient to lose your kids. She stays awake for hours, lavender scrubs folded within the trunk, listening for footsteps, any signal of bother. Her shift begins quickly. She’ll stroll into the hospital exhausted, pretending every thing is ok.

Throughout the nation, women and men sleep of their autos night time after night time after which head to work the subsequent morning. Others scrape collectively sufficient for every week in a motel, realizing one missed paycheck might go away them on the road.

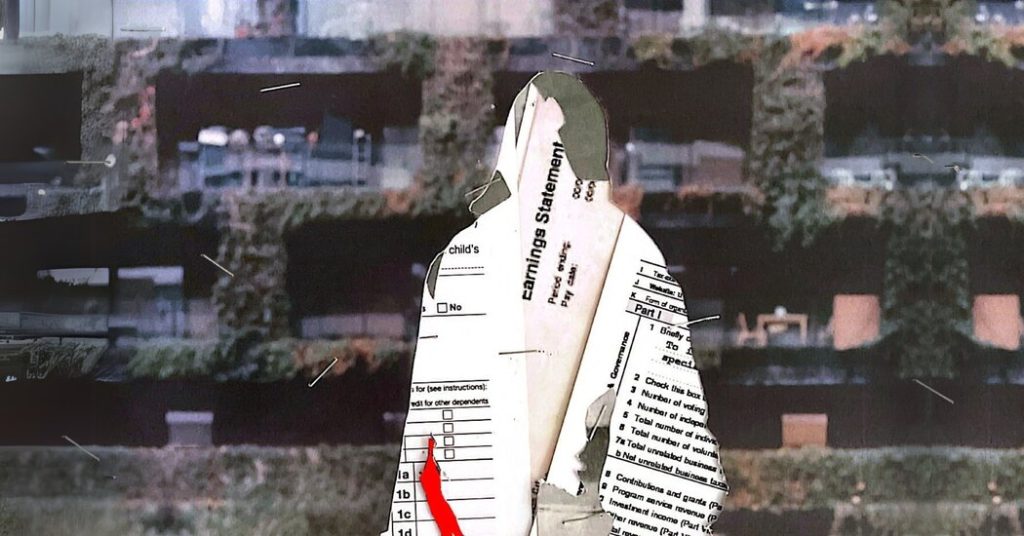

These persons are not on the fringes of society. They’re the employees America relies on. The very phrase “working homeless” ought to be a contradiction, an impossibility in a nation that claims arduous work results in stability. And but, their homelessness will not be solely pervasive but additionally persistently missed — excluded from official counts, ignored by policymakers, handled as an anomaly reasonably than a catastrophe unfolding in plain sight.

At this time, the specter of homelessness is most acute not within the poorest areas of the nation, however within the richest, fastest-growing ones. In locations like these, a low-wage job is homelessness ready to occur.

For an rising share of the nation’s work drive, a mixture of hovering rents, low wages and insufficient tenant protections have compelled them right into a brutal cycle of insecurity by which housing is unaffordable, unstable or totally out of attain. A current examine analyzing the 2010 census discovered that almost half of individuals experiencing homelessness whereas staying in shelters, and about 40 % of these dwelling open air or in different makeshift situations, had formal employment. However that’s solely a part of the image. These numbers don’t seize the total scale of working homelessness in America: the numerous who lack a house however by no means enter a shelter or who wind up on the streets.

I’ve spent the previous six years reporting on women and men who work in grocery shops, nursing houses, day care facilities and eating places. They put together meals, inventory cabinets, ship packages and take care of the sick and aged. And on the finish of the day, they return to not houses however to parking heaps, shelters, the crowded residences of associates or kinfolk and squalid extended-stay resort rooms.

America has been experiencing what economists described as a traditionally tight labor market, with a nationwide unemployment price of simply 4 %. And all of the whereas, homelessness has soared to the very best stage on report.

What good is low unemployment when employees are a paycheck away from homelessness?

Just a few statistics succinctly seize why this disaster is unfolding: At this time there isn’t a single state, metropolis or county in the US the place a full-time minimum-wage employee can afford a median-priced two-bedroom condominium. An astounding 12.1 million low-income renter households are “severely price burdened,” spending no less than half of their earnings on lease and utilities. Since 1985, lease costs have exceeded earnings positive aspects by 325 %.

Based on the Nationwide Low Revenue Housing Coalition, the common “housing wage” required to afford a modest two-bedroom rental house throughout the nation is $32.11, whereas practically 52 million American employees earn lower than $15 an hour. And should you’re disabled and obtain S.S.I., it’s even worse: These funds are at present capped at $967 a month nationwide, and there’s hardly anyplace within the nation the place this type of mounted earnings is sufficient to afford the common lease.

However it’s not simply that wages are too low; it’s that work has develop into extra precarious than ever. Even for these incomes above the minimal wage, job safety has eroded in ways in which make steady housing more and more out of attain.

Increasingly employees now face risky schedules, unreliable hours and a scarcity of advantages akin to sick go away. The rise of “simply in time” scheduling means workers don’t know what number of hours they’ll get week to week, making it inconceivable to finances for lease. Complete industries have been gigified, leaving ride-share drivers, warehouse employees and temp nurses working with out advantages, protections or dependable pay. Even full-time jobs in retail and well being care — as soon as seen as reliable — are more and more contracted out, become part-time roles or made contingent on assembly ever-shifting quotas.

For tens of millions of People, the best risk isn’t that they’ll lose their jobs. It’s that the job won’t ever pay sufficient, by no means present sufficient hours, by no means provide sufficient stability to maintain them housed.

It’s not simply in New York and San Francisco and Los Angeles. It’s additionally in tech hubs like Austin and Seattle, cultural and monetary facilities like Atlanta and Washington, D.C., and quickly increasing cities like Nashville, Phoenix and Denver, locations awash in funding, luxurious growth and company progress. However this wealth isn’t trickling down. It’s pooled on the prime, whereas reasonably priced models are demolished, new ones are blocked, tenants are evicted — about each minute, seven evictions are filed throughout the US, based on Princeton’s Eviction Lab — and housing is handled as a commodity to be hoarded and exploited for max revenue.

This ends in a devastating sample: As cities gentrify and develop into “revitalized,” the nurses, academics, janitors and little one care suppliers who preserve them working are being systematically priced out. In contrast to in earlier intervals of widespread immiseration, such because the recession of 2008, what we’re witnessing right this moment is a disaster born much less of poverty than of prosperity. These employees aren’t “falling” into homelessness. They’re being pushed. They’re the casualties not of a failing economic system however of 1 that’s thriving — simply not for them.

And but, at the same time as this calamity deepens, many households stay invisible, present in a form of shadow realm: disadvantaged of a house, however neither counted nor acknowledged by the federal authorities as “homeless.”

This exclusion was by design. Within the Nineteen Eighties, as mass homelessness surged throughout the US, the Reagan administration made a concerted effort to form public notion of the disaster. Officers downplayed its severity whereas muddying its root causes. Federal funding for analysis on homelessness was steered nearly solely towards research that emphasised psychological sickness and dependancy, diverting consideration from structural forces — gutted funding for low-income housing, a shredded security web. Framing homelessness on account of private failings didn’t simply make it simpler to dismiss; it was additionally much less politically threatening. It obscured the socioeconomic roots of the disaster and shifted blame onto its victims. And it labored: By the late Nineteen Eighties, no less than one survey confirmed that many People attributed homelessness to medicine or unwillingness to work. No one talked about housing.

Over the a long time, this slim, distorted view continued, embedding itself within the federal authorities’s annual homeless census. Earlier than one thing could be counted, it have to be outlined — and a technique the US has “diminished” homelessness is by defining whole teams of the homeless inhabitants out of existence. Advocates have lengthy decried the census’ intentionally circumscribed definition: solely these in shelters or seen on the streets are tallied. In consequence, a comparatively small however conspicuous fraction of the whole homeless inhabitants has come to face, within the public creativeness, for homelessness itself. Everybody else has been written out of the story. They actually don’t depend.

The hole between what we see and what’s actually occurring is huge. Current analysis means that the true variety of folks experiencing homelessness — factoring in these dwelling in automobiles or motel rooms, or doubled up with others — is no less than six occasions as excessive as official counts. As dangerous because the reported numbers are, the truth is way worse. The tents are simply the tip of the iceberg, essentially the most obtrusive signal of a much more entrenched disaster.

This willful blindness has induced incalculable hurt, locking tens of millions of households and people out of important help. However it’s completed greater than that. How we depend and outline homelessness dictates how we reply to it. A distorted view of the issue has led to responses which are insufficient at greatest and cruelly counterproductive at worst.

However the fact is that every one of this — the nights spent sleeping in automobiles, the fixed uprooting from motels to associates’ couches, the incessant hustle to remain one step forward of homelessness — is neither inevitable nor intractable. Ours doesn’t should be a society the place folks clocking 50 or 60 hours every week aren’t paid sufficient to satisfy their most elementary wants. It doesn’t should be a spot the place mother and father promote their plasma or stay with out electrical energy simply to maintain a roof over their kids’s heads.

For many years, lawmakers have stood by whereas rents soared, whereas housing was become an asset class for the rich, whereas employee protections have been shredded and wages didn’t sustain. We’ve settled for piecemeal, better-than-nothing initiatives that tweak the prevailing system reasonably than rework it. However the catastrophe we face calls for greater than half measures.

It’s not sufficient to drag folks out of homelessness — we should cease them from being pushed into it within the first place. In some cities, for each one one who secures housing, one other estimated 4 develop into homeless. How can we halt this relentless churn? There are instant steps: stronger tenant protections like lease management and just-cause eviction legal guidelines, the elimination of exclusionary zoning, and better wages with sturdy labor protections. However we additionally want transformative, complete options, like large-scale investments in social housing, that deal with reasonably priced, dependable shelter as an important public good, not a privilege for the few.

Any significant resolution would require a basic shift in how we take into consideration housing in America. A secure, reasonably priced house shouldn’t be a luxurious. It ought to be a assured proper for everyone. Embracing this concept will demand an enlargement of our ethical creativeness. Performing on it would require unwavering political resolve.

We ought to be asking ourselves not simply how a lot worse this may develop into but additionally why we’ve tolerated it for thus lengthy.

As a result of when work now not supplies stability, when wages are too low and rents are too excessive, when tens of millions of persons are one medical invoice, one missed paycheck, one lease hike away from shedding their houses — who, precisely, is secure?

Who will get to really feel safe on this nation? And who’re the casualties of our prosperity?