Guide Evaluation

Paris in Ruins: Love, Battle, and the Start of Impressionism

By Sebastian Smee

Norton: 384 pages, $35

When you purchase books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist unbiased bookstores.

Guide Evaluation

Monet: The Stressed Imaginative and prescient

By Jackie Wullschläger

Knopf: 576 pages, $45

When you purchase books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist unbiased bookstores.

Revolution was within the plein air. In the course of the reign of Napoleon III, the Second French Empire had colonized extensively overseas and modernized at house, with the development of Paris’ boulevards and town’s superb ascent as the worldwide capital of tradition and style. The empire had introduced a stability to France after many years of bloodshed and tumult, however republican passions nonetheless stirred, significantly amongst mental elites and haute bourgeoisie.

What occurred on the street to revolt? This 12 months marks the sesquicentennial anniversary of the debut Impressionist present in 1874, and two beautiful books have arrived to toast the event. Whereas they differ in scope, each are sleek, fluent, resonant additions to artwork historical past.

A critic on the Monetary Instances, Jackie Wullschläger has written a luxurious biography of Claude Monet, the motion’s maestro, limning the innovation beneath his surfaces. “Monet: The Stressed Imaginative and prescient” spans the painter’s prolonged life and profession, a portrait of an artist mercurial and materialist, bold and immodest, but unstintingly loyal to all in his orbit. She traces his middle-class background as a baby and adolescent in seaside Le Havre, water his everlasting muse. He selected a much less profitable career, backed by a beloved aunt and better-off buddies, akin to Édouard Manet. Within the 1860s he gravitated towards Manet’s circle in Paris: Degas, Bazille, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Pisarro and Renoir. Now lodestars of museums and personal collections, these painters buttressed each other through the lean months, the haves tending to the have-nots, united of their distaste for the Salon’s stale, imperious standards. (Monet ultimately owned 14 Cézanne canvases.)

Because the Franco-Prussian Battle commenced, Monet decamped to London, the place he sat out the hostilities, palette in hand. Upon his return to France, he and his colleagues labored outside, usually setting their easels aspect by aspect. Monet relied on his first spouse, Camille, as his main mannequin; she posed as 4 distinct figures in his early “Ladies within the Backyard” (1866). “The Port at Argenteuil” (1874), Wullschläger observes, is “a beacon of the primary Impressionist second. Unified, each half to each different, inviting the attention to enter and linger anyplace, satisfying in its ornamental meeting of varieties, the arabesques of timber echoing the cloud shapes, it evokes a harmonious environment fairly completely different from the tough depiction of the damaged bridge just a few months earlier than.”

After Camille’s extended sickness and demise in 1879, Monet took up with Alice Hoschedé, the estranged partner of a department-store magnate whose demise allowed the couple to wed, merging their households, a bohemian Brady Bunch. Their villa at Giverny remained a base of operations all through their lives.

Jackie Wullschläger, writer of “Monet: The Stressed Imaginative and prescient.”

(William Cannell)

Because the century waned, Monet grew bolder: He launched into a number of sequence of topics portrayed at completely different hours of day, in diversified casts of sunshine. Wullschläger underscores “Haystacks” as a breakthrough, insisting on “contemplation of that second passing, of the transience of all moments.” She writes: “The brief staccato strokes produce waves of color in a number of layers, suggesting gentle as a pulsing pressure, but mixing into an opalescent haze seen from a distance.” Towards a backdrop of postwar consolation, recent methods of seeing emerged.

Wullschläger avoids making an attempt an exhaustive account; why overwhelm her guide with gratuitous particulars? She prefers to thrill, saving one of the best for final: her sweeping research of Monet’s magnificent water lilies (he known as them “Grandes Décorations”), a blaze of brushwork, conflating illustration and abstraction, heralding such future titans as Pollock and de Kooning. “The Grandes Décorations have the traits of a late type: excessive, abstracting, inside,” Wullschläger notes, “directly the crowning achievement of Impressionism, eloquent work … the all-over compositions talking of chaos and dissolution.” Regardless of failing eyesight, Monet saved working till his demise in 1926.

Sebastian Smee, writer of “Paris in Ruins.”

(Amber Davis Tourlentes)

Sebastian Smee, the Washington Submit’s Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, departs from Wullschläger’s method in his vibrant and incisive “Paris in Ruins,” tightening his aperture to these pivotal years simply previous to that preliminary exhibition, when the Franco-Prussian Battle toppled the Second Empire and birthed, in matches and begins, France’s Third Republic. Poised on the guide’s middle is the romance between the married Édouard Manet and the gifted Berthe Morisot, single and dwelling along with her dad and mom within the posh suburb of Passy. Manet had galvanized essentially the most creative (and disruptive) painters and writers, drawing them like a magnet. “He was just like the director of an novice theater troupe made up of buddies, household, and anybody he might rope in,” Smee opines. “They wore their assigned costumes with various levels of conviction, addressing an viewers that was assumed to be within the recreation.”

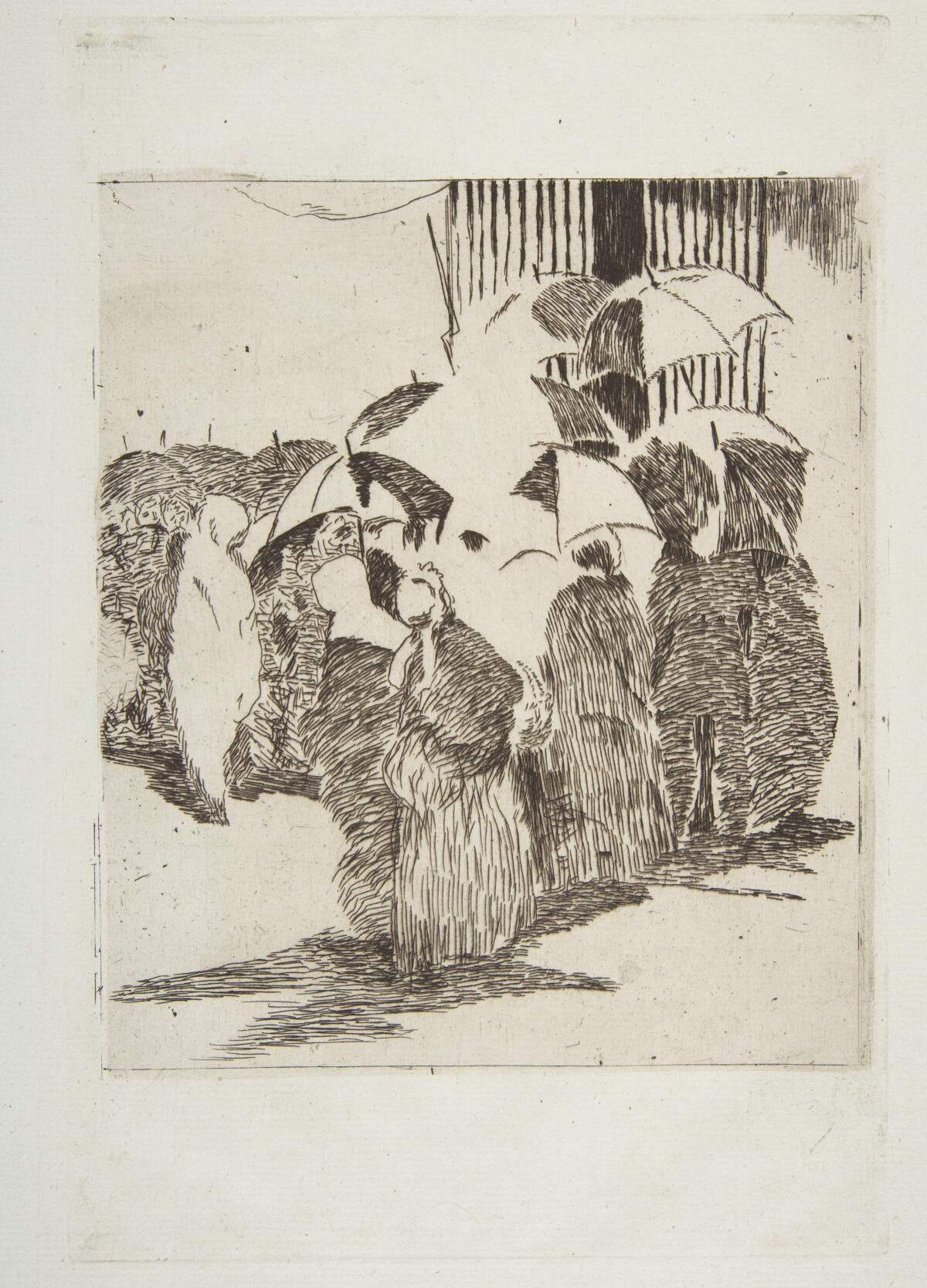

Édouard Manet’s “Line in Entrance of the Butcher Store.”

(Courtesy of Norton)

Manet’s infatuation with Morisot first manifested in his homage to Goya, “The Balcony” (1868-69). “Paris in Ruins” brims with scrumptious anecdotes: the Morisots’ genteel gatherings; army responsibility imposed on eligible males; the hot-air balloons and provider pigeons that preserved town’s communication with the world. With a treaty on the desk, through which Napoleon would give up and finish the Franco-German Battle, civil struggle broke out in France, pitting leftists towards moderates in cahoots with the German chief. Smee’s re-creation of this difficult second and the revolt it ignited is excellent, scalp-tingling narration, culminating with Bloody Week in Could 1871, which yielded hundreds of civilian casualties, random executions and torching of iconic establishments.

Because the Metropolis of Gentle smoldered, this cadre of artists swerved towards tranquil landscapes and home scenes that exalted bourgeois values. Theirs was an insurgency nonetheless. “The absence of hierarchy prolonged to even technical concerns: the Impressionists painted straight onto the canvas slightly than with varnish layered over glazes layered over paint layered over drawing,” Smee notes. “Impressed by Japanese prints, they tried to keep away from compositions that appeared too calculated, picturesque, or sedately symmetrical. They welcomed overlapping visible phenomena, akin to timber obscuring buildings. … There was no shading, no modeling, and due to this fact no depth. Generally it was as if these landscapes have been considered … from a balloon, or by an individual with one eye.” Smee captures the intimacy of Manet and Morisot’s pas de deux, however finally “Paris in Ruins” belongs to the woman. The writer argues that her affect was higher than artwork historical past has acknowledged.

Simply because the Impressionists liberated easel portray from the treacly educational kinds prized by the Salon, Smee and Wullschläger liberate Impressionism from the clichés of dorm-room posters and greeting-card sentimentality. These artists have been — and are — radical: Picasso rejected their concepts, however he’s unthinkable with out them, linked via Cézanne, Van Gogh and the Fauves. Each authors discover the luminosity on the motion’s coronary heart and brilliantly amplify it on the web page.

Hamilton Cain is a guide critic and the writer of a memoir, “This Boy’s Religion: Notes From a Southern Baptist Upbringing.” He lives in New York.