The Santa Ana winds had been already blowing arduous after I ran the primary worm simulation. I’m no hacker, nevertheless it was straightforward sufficient: Open a Terminal shell, paste some instructions from GitHub, watch characters cascade down the display. Identical to within the motion pictures. I used to be scanning the passing code for recognizable phrases—neuron, synapse—when a buddy got here to choose me up for dinner. “One sec,” I yelled from my workplace. “I’m simply operating a worm on my laptop.”

On the Korean restaurant, the power was manic; the wind was bending palm bushes on the waist and sending purchasing carts skating throughout the car parking zone. The ambiance felt heightened and unreal, like a podcast at double pace. You’re doing, what, a cybercrime? my buddy requested. Over the din, I attempted to clarify: No, not a worm like Stuxnet. A worm like Richard Scarry.

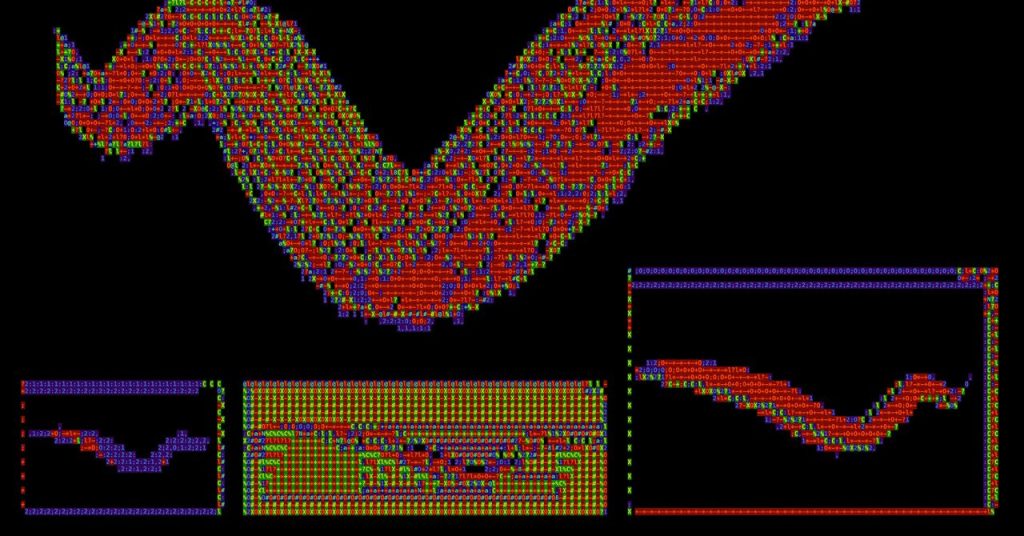

By the point I obtained residence it was darkish, and the primary sparks had already landed in Altadena. On my laptop computer, ready for me in a volumetric pixel field, was the worm. Pointed at every finish, it floated in a mist of particles, eerily stick-straight and immobile. It was, after all, not alive. Nonetheless, it appeared deader than useless to me. “Bravo,” mentioned Stephen Larson, after I reached him later that night time. “You have got achieved the ‘hiya world’ state of the simulation.”

Larson is a cofounder of OpenWorm, an open supply software program effort that has been making an attempt, since 2011, to construct a pc simulation of a microscopic nematode known as Caenorhabditis elegans. His purpose is nothing lower than a digital twin of the actual worm, correct all the way down to the molecule. If OpenWorm can handle this, it might be the primary digital animal—and an embodiment of all our data not solely about C. elegans, which is without doubt one of the most-studied animals in science, however about how brains work together with the world to provide conduct: the “holy grail,” as OpenWorm places it, of programs biology.

Sadly, they haven’t managed it. The simulation on my laptop computer takes information culled from experiments carried out with residing worms and interprets it right into a computational framework known as c302, which then drives the simulated musculature of a C. elegans worm in a fluid dynamic atmosphere—all in all, a simulation of how a worm squiggles ahead in a flat plate of goo. It takes about 10 hours of compute time to generate 5 seconds of this conduct.

A lot can occur in 10 hours. An ember can journey on the wind, down from the foothills and into the sleeping metropolis. That night time, on Larson’s recommendation, I tweaked the time parameters of the simulation, pushing past “hiya world” and deeper into the worm’s uncanny valley. The following morning, I woke to an eerie orange haze, and after I pulled open my laptop computer, bleary-eyed, two issues made my coronary heart skip: Los Angeles was on fireplace. And my worm had moved.

At this level, you might be asking your self a really affordable query. Again on the Korean place, between bites of banchan, my buddy had requested it too. The query is that this: Uhh … why? Why, within the face of the whole lot our precarious inexperienced world endures, of all the issues on the market to unravel, would anybody spend 13 years making an attempt to code a microscopic worm into existence?