The officers handled journalist Saint Mienpamo Onitsha as if he was violent and harmful. Weapons drawn, they arrested him on the house of a buddy, drove him to the native police station in Nigeria’s southern Bayelsa State, after which flew him to the nationwide capital, Abuja.

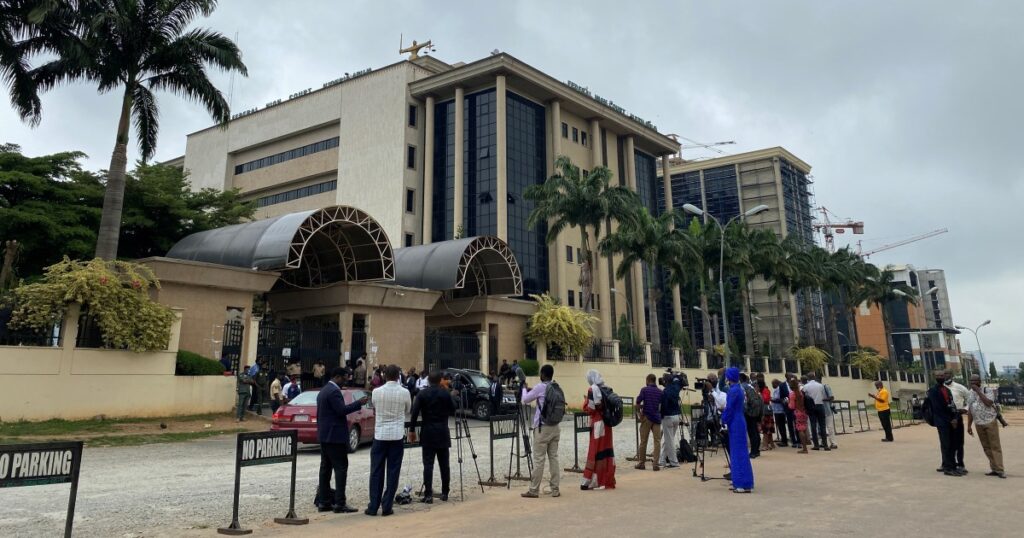

Per week later, they charged Onitsha underneath the nation’s 2015 Cybercrimes Act and detained him over his reporting about tensions within the oil-rich Niger Delta area. This was in October 2023. He was launched on bail in early February and is because of seem earlier than a courtroom on June 4.

The Cybercrimes Act is tragically acquainted to Nigeria’s media neighborhood. Since its enactment, not less than 25 journalists have confronted prosecution underneath the regulation, together with 4 arrested earlier this yr. Anande Terungwa, a lawyer for Onitsha, described the regulation to me as a device misused to “hunt journalists”.

For years, media and human rights teams had been calling for the act to be amended to forestall its misuse as a device for censorship and intimidation. Then, in November final yr, Nigeria’s Senate proposed amendments and held a public listening to to assist form adjustments. The Committee to Shield Journalists (CPJ), alongside different civil society and press teams, submitted beneficial reforms.

On February 28, Nigerian President Bola Tinubu signed amendments to the act, together with revisions to a bit criminalising expression on-line, in keeping with a duplicate of the regulation shared with me by Yahaya Danzaria, the clerk of Nigeria’s Home of Representatives. The adjustments, which have but to be revealed within the authorities gazette, have buoyed hopes for improved press freedom, however the regulation continues to go away journalists liable to arrest and surveillance.

“It’s higher, nevertheless it’s positively not the place we wish it to be,” Khadijah El-Usman, senior packages officer with the Nigeria-based digital rights group Paradigm Initiative, advised me in a telephone interview in regards to the amended regulation. “There are nonetheless provisions that may be taken benefit of, particularly by these in energy.”

One of many major considerations has been Part 24 of the regulation, which defines the crime of “cyberstalking”. It’s this part that authorities repeatedly used to cost journalists, and it is likely one of the sections that was amended.

Below the earlier model of the regulation, Part 24 criminalised using a pc to ship messages deemed “grossly offensive, pornographic or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character”, and punished such offences with as much as three years in jail and a fantastic. The identical punishment utilized for sending knowingly false messages “for the aim of inflicting annoyance” or “useless anxiousness”. In apply, this meant journalists risked jail time based mostly on extremely subjective interpretations of on-line reporting.

The amended model maintains the heavy penalty, however refines the offence as laptop messages which are pornographic or knowingly false, “for the aim of inflicting a breakdown of regulation and order, posing a risk to life, or inflicting such messages to be despatched”. Whereas the narrower language is welcome, the likelihood for abuse stays.

“It may have been extra particular in wording,” Solomon Okedara, a Lagos-based digital rights lawyer, advised me after reviewing the amended part. He mentioned it was an enchancment as a result of the burden of proof to carry costs is greater, however nonetheless leaves room for authorities to make arrests on claims that sure reporting has induced a “breakdown of regulation and order”.

It stays to be seen precisely how these adjustments will have an effect on the circumstances of journalists and others beforehand charged underneath now-amended sections. “It’s now for the legal professionals to make use of,” Danzaria defined. “You can’t use an previous regulation to prosecute any person…if [the case] is ongoing, the brand new regulation supersedes no matter was in place.”

For Onitsha’s case, Terungwa mentioned he would search to include the amendments into his defence in courtroom. CPJ continues to name for authorities to drop all prison prosecutions of journalists in reference to their work.

One other problem with the regulation – even after the current amendments – is the way it could allow surveillance abuses. Part 38 of Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Act fails to explicitly require regulation enforcement to acquire a court-issued warrant earlier than accessing “visitors knowledge” and “subscriber info” from service suppliers. This oversight hole is especially regarding given how Nigeria’s police have used journalists’ name knowledge to trace and arrest them.

“I’m trying in direction of a future cybercrimes act that respects human rights,” El-Usman emphasised, noting the necessity for legal guidelines that guard in opposition to abuses, not simply in Nigeria, however throughout the area. From Mali to Benin to Zimbabwe, authorities have used cybercrime legal guidelines and digital codes to arrest reporters for his or her work. Journalists’ privateness can also be broadly underneath risk.

Nigeria’s lawmakers have confirmed they’ll act to enhance freedom of the press and expression of their nation, however journalists stay in danger. Those self same lawmakers have the chance to make additional reforms that might defend the press domestically and ship a rights-respecting message past their borders. Will they seize it?

The views expressed on this article are the writer’s personal and don’t essentially replicate Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.