“Ain’t I a lady?” Properly, no, I’m not.

But ever since I first learn that chorus in Sojourner Fact’s well-known speech to the 1851 Girl’s Rights Conference in Akron, Ohio, I’ve considered it as belonging to the canon of nice American rhetoric — proper up there with Abraham Lincoln’s “With malice towards none” and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I’ve a dream.”

It’s for that cause that I cited the road in my April 8 column for example of the sort of American spirit I treasure — what I known as “the shared conviction that sturdy and weak are united in a standard democratic creed.”

The issue — as I discovered after the column was revealed — is that Fact could by no means have stated it.

We could by no means know for positive. A near-contemporaneous transcript of the speech, revealed in June 1851 within the Anti-Slavery Bugle newspaper, doesn’t include the well-known phrase. Nevertheless it did seem (as “And ar’n’t I a lady?”) 12 years later, in a really completely different model of the speech revealed by the feminist abolitionist Frances Dana Barker Gage, who had presided over the conference.

Among the many causes to not imagine Gage’s account: Her model of Fact’s speech is rendered in a Southern dialect. However Fact was born in upstate New York as a slave to a Dutch-speaking household, and spoke English with a Dutch accent.

Regardless of the case, each variations of the speech are highly effective and ring true, morally talking, and Fact’s place within the pantheon of American heroes stays safe.

There are additionally less-heralded heroes within the American story, together with two who got here to my consideration this week virtually accidentally.

In my column, I famous among the names that appeared on the passenger manifest of the ship — the M.V. Italia — that introduced my mom to the US as a 10-year-old refugee in 1950. Amongst them was Gerda Nesselroth, then 45, who was listed as “stateless.” She arrived alongside together with her 15-year-old son, Peter, whose identify seems beneath hers on the manifest.

The day after my column was revealed, I acquired an e-mail from Peter’s daughter, Eva Nesselroth Woyzbun of Toronto. Eva steered me towards a short biography of her dad from the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program, produced by the Azrieli Basis. He was born in Berlin in 1935 and fled to Antwerp, Belgium, after Kristallnacht. Following the Nazi invasion in 1940, the household went into hiding however had been betrayed in 1944. Peter managed to be smuggled to security in Switzerland, whereas Gerda and his father, Laslo, had been deported to Auschwitz. Solely Gerda made it out alive: Eva known as her “the hardest human I’ll ever know.”

In America, Peter earned a Ph.D. at Columbia and spent most of his profession as a distinguished professor of French and comparative literature on the College of Toronto. However, as Eva wrote to me, he “by no means acquired Canadian citizenship — he was dedicated to the venture of turning into and being ‘American’ and noticed himself as nothing however. The mythology of America sustained him.”

Eva added this: “Have been he alive as we speak” — he died in 2020 — “he’d be terrified for these the Trump administration is rounding up and deporting, having spent his personal childhood residing in hiding and on the run.”

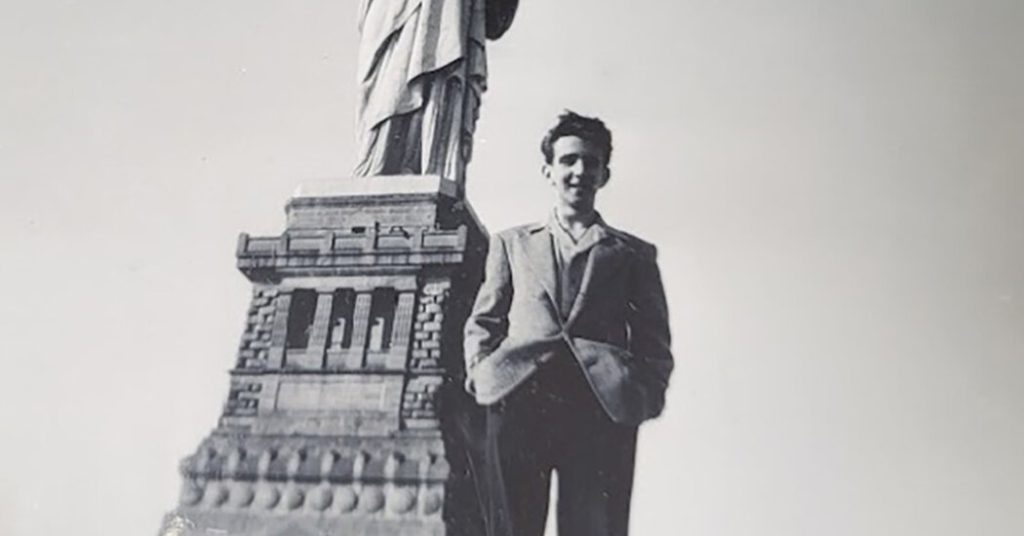

Eva despatched me an image of her father, newly arrived in the US, standing earlier than the Statue of Liberty. Could his reminiscence be for a blessing — and so will be the reminiscence of what America used to face for.